Select the right species for each field

John Harris of Oliver Seeds explains how dairy producers can make the best choice of seeds mixture

The wet winter of 2019/2020 meant many dairy farmers were faced with a pond in every field in spring, which quickly turned into drought eight weeks later.

Many of the easily leachable nutrients were just not there for the grass when it needed to start growing. The rapid swing from wet weather to cold and dry put even more stress on plants. Even in soils with good nutrient levels, their mobility was affected. Crops took a long time to recover and yields were drastically affected, in particular first cut silage.

If water can escape a field easily, faster recovery can happen – so field drainage and ditch maintenance cannot be ignored. Any compaction must also be alleviated, as hard layers in the topsoil can prevent water escaping. In silage fields, adopting a controlled traffic system with permanent routes for tractors to follow, rather than allowing them to travel randomly across the field, can reduce compaction up to 80% across a field.

Continuing to grow the same species and same mixtures as have been grown over the past 20 years is not a good plan. Times have changed and the types of grass and forage grown are also changing.

Select species that are best able to survive and thrive in each individual field, bearing in mind soil type, geography, average rainfall, stocking levels, fertiliser input and how long it will be in production.

Do not be misled by outdated views on species that have been improved by plant breeders in recent years, such as Donata cocksfoot, which is soft-leaved and palatable, unlike the courser varieties of yesteryear. Deep-rooted Donata coped well last year, better able to perform in stressful conditions, wet or dry, than many perennial ryegrasses.

Newer festuloliums such as Perseus and the longer-term Fojtan, which are crosses that combine the beneficial characteristics of ryegrasses and fescues, also demonstrated good spring growth where straight ryegrasses struggled. They also had far better leaf retention in the dry summer.

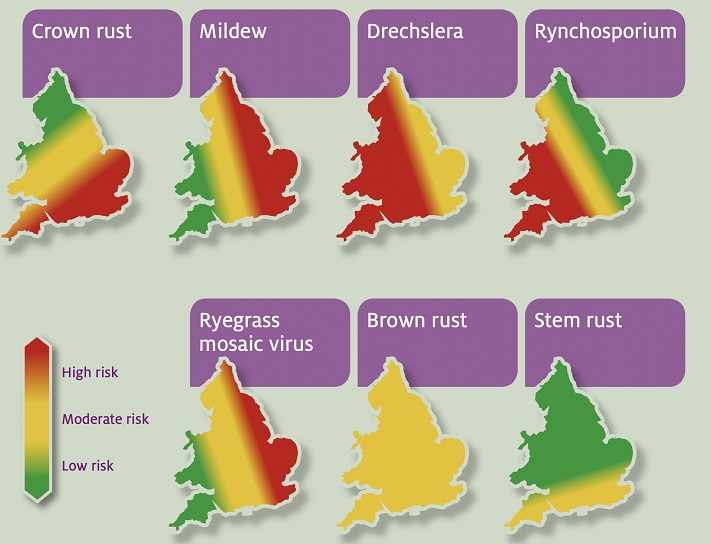

Another factor exposed by extremes of weather is the disease resistance of individual varieties. Resistance ratings to diseases such as crown rust and drechslera can be found in the Recommended Grass and Clover Lists published each year. For example, the south of England and Wales is high risk for crown rust, the east of England for mildew and Wales, south and central England for drechslera.

Data from the Recommended Grass and Clover List, full data at www.britishgrassland.com

Data from the Recommended Grass and Clover List, full data at www.britishgrassland.com

Disease severity is very dependent on the weather in each season. Some diseases are more prevalent in the wetter, warmer areas, while other are more common in drier locations. In some areas more than one disease is a risk. In these areas selecting varieties with high disease resistance, for example Perseus which scores a 9 for crown rust resistance, is essential.

Any young plant thrives when it is fed correctly – so do not be mean with the fertiliser, especially in the early years. Young plants with roots near the surface will take a while to reach any ploughed in manures, so applying the right amount of seedbed fertiliser is crucial to good establishment.

Multi-species leys

There is a definite trend towards sowing diverse leys filled with herbs and legumes as well as grasses. This not only widens the nutritional composition of the forage but usually also provides deeper and varied rooting depth, aiding drought tolerance and improving soil conditioning.

Be prepared to carry out as much weed control as possible before sowing multi-species leys as there are very few chemical solutions to weed invasion in these swards. Preparing a false seedbed two to four weeks before the planned sowing date, to encourage a flush of weed seedlings which can be controlled, may be seen as an inconvenience and a delay. However, the rewards can be significant in terms of establishing the desired species and the subsequent quality of the forage.

Popular herb species include chicory, which is fast to establish, deep-rooted and drought resistant. It also has anthelmintic properties to help reduce worm burdens in animals. It is high in protein, minerals and trace elements, but needs regular grazing and should not be used in hay or silage fields because of its coarse woody stem.

Ribwort plantain, Sheep’s Burnet, Sheep’s Parsley all have long tap roots making them good in dry conditions, while Yarrow has rhizomatous growth and grows well in any soil. Legumes including Red clover, Sainfoin and lucerne are being grown more and more for the depth of their roots and their nitrogen-fixing properties. Some dairy farmers are growing these in an attempt to reduce their reliance on bought-in protein.

Flood-risk

While drought might be a problem on many farms, so a high water-table and flooding is the issue for others. I have seen lucerne rot off in saturated fields where it was a top yielding crop the previous year and ryegrass that had had 150kg of nitrogen looking like it had had none.

Oliver Seeds has developed a Flood Meadow mixture including species such as Timothy, Meadow Fescue, Festulolium and Alsike clover, that can better deal with occasional immersion than ryegrass can.

Undersowing maize with grass or establishing Italian Ryegrass after maize has been cut is being practiced increasingly in fields growing continuous maize. The main reasons are to reduce soil loss in wet weather and nitrogen leaching, to make less damage at harvest and also the opportunity to get an extra crop of grass before the next maize crop is sown. This is still at an early stage of development, with most farmers looking at different systems and mixtures to achieve this goal.

Time spent walking and checking grass fields above and below ground will always be rewarded. Breaking the farm into manageable blocks and heading off with a spade and a notebook can turn this into a less daunting task.

The priority for dairy farmers – be they extended grazers or if they cut and cart all their grass to housed cows, is to produce consistent yields of high-quality forage that meet the demands of their livestock. Those that do so, whilst also being flexible and taking widely varying weather conditions into account, will be best placed to face whatever the climate throws at them in future.

This article first appeared in the March 2021 issue of CowManagement magazine

The Recommended Grass and Clover List is supported by BSPB, AHDB and HCC